GottaGo! article in the Glebe Report, May 2020 issue, page 2; and Mainstreeter, June 2020, page 16.

More than ever, COVID 19 has made clear that a network of clean, safe and accessible public toilets is fundamentally a public health issue.

Recent media attention to truckers, taxi or uber drivers, bus drivers, garbage collectors, delivery persons, journalists, photographers and anyone doing essential jobs that involve moving around the city, has highlighted this problem. What are they supposed to do when the public toilets that do exist are all closed during this pandemic? Normally, these people use public toilets or facilities at businesses (cafes, eateries), but these are now closed as well.

People who are homeless have always had a problem, but it’s worse now that there is ‘no place to go.’ This includes access to water for handwashing, something we are told to do frequently. For many people experiencing homelessness, access to clean running water and disinfectants is not a given. They may need to walk several city blocks or further to reach the nearest public restroom.

And then there’s the rest of us. While being told to stay home, we’re also encouraged to go out for walks to get exercise and fresh air. What to do when we need a toilet? Can we tell a small child to ‘hold it’ until they get home? Must such walks be unavailable to those with chronic diseases, such as Crohn’s and Colitis, that require readily available facilities? Menstruating women caught short? Older adults whose bladders require more frequent attention?

In the Glebe, the NCC opened Queen Elizabeth drive for walkers and bikers, a positive move. But there are no public toilets, and facilities at Patterson Creek and the Canal Ritz, for example, are generally closed. And even when these facilities are open, there is no signage.

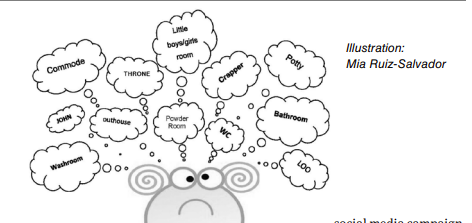

The banality of the subject means we don’t often consider public toilets as a basic human right as they should be. Arguments exist for the human right to shelter, food and water in the city — but what happens after that? Toilets are something everybody needs.

Why is building and maintaining roads considered an unquestionable necessity and legitimate expense, but having public toilets is deemed a superfluous luxury, asks Andre Picard. The answer is not to refuse to build public toilets, it is to value and maintain them as any other public infrastructure.

In Canada, continues Picard, we behave as if urination, defecation and menstruation are not routine bodily functions, but are somehow optional if we are away from our homes. Toilets need to be considered a No. 1 (and No. 2) priority of urban design; they are essential for an inclusive, healthy society. We design, construct and maintain public spaces such as roads, sidewalks and parks, but act as if people using those spaces will never need toilet facilities unless they are attending an “event” such as Canada Day, and you need to content yourself with a long line-up to use a porta-potty that requires you to hold your breath.

What’s the most intimate way you engage with your city’s architecture? Answer: when you go to the toilet. Real cities give their people places to pee.

The GottaGo! Campaign has been advocating for a network of clean, safe and accessible, public toilets in Ottawa since 2014. Though there have been some notable successes (e.g.: public toilets in the node stations of the LRT; porta potties at some splash pads and sports fields), our pleas have been pushed aside as too expensive, an ‘extra’ compared to other infrastructure.

And, here we are, in the midst of an historic pandemic. Maybe this is what it takes to get some serious attention to the issue of public health, including toilets. A crisis can be an opportunity, so now is the time for all of us to advocate for a network of public toilets, to include running water and soap for handwashing.

For centuries, we have known that sanitation is key to a healthy population. For example, the 2007 World Health Report entitled Evolution of Public Health Security concludes that from the 7th century onwards, quarantine, sanitation and immunization have been the three main advances in strengthening public health. Yet, for decades, we have ignored this issue in terms of the availability of public toilets in Ottawa.

For the past 6 years, the GottaGo! campaign has been tirelessly pressuring the City of Ottawa and National Capital Commission to do something about this issue. Please help us in advocating for a network of clean, safe and accessible public toilets in the City that we call home.

For details, please visit GottaGo! website.

The GottaGo! campaign core team (Bessa Whitmore, Lui Kashungnao, Eric McCabe, Kristina Ropke, Alan Etherington, Zeinab Mohamed, Nick Aplin)